Jole Veneziani. High Fashion and Society In Milan.

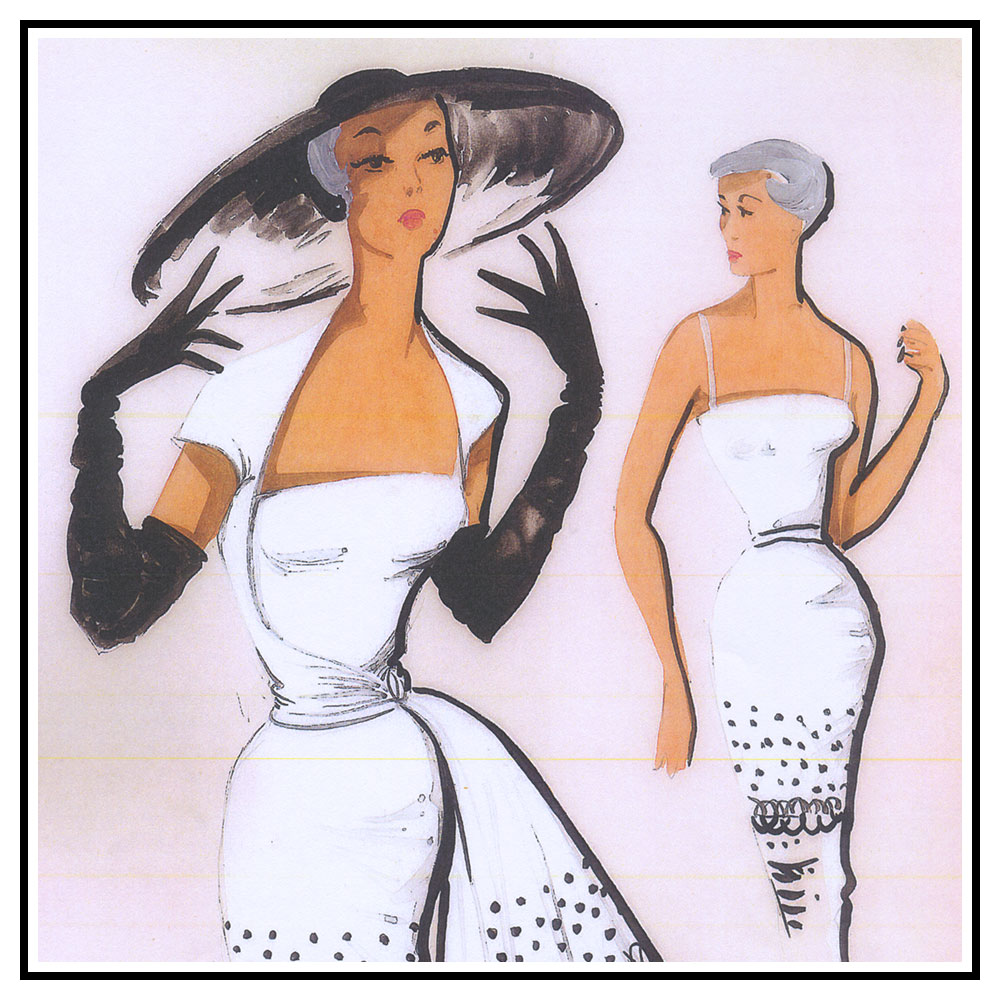

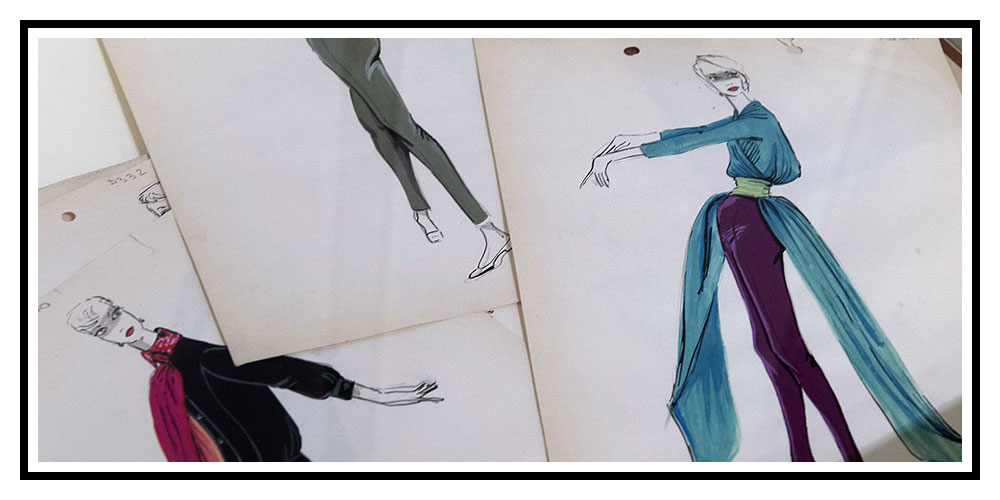

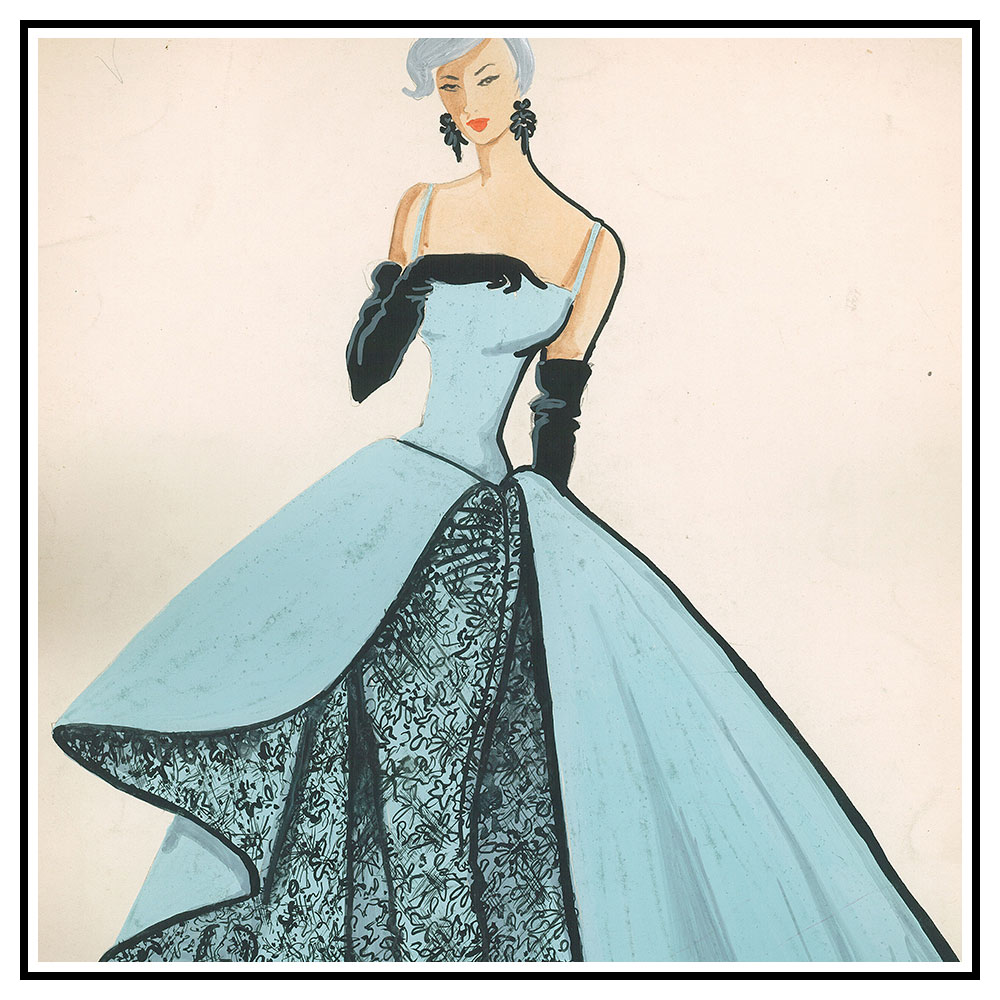

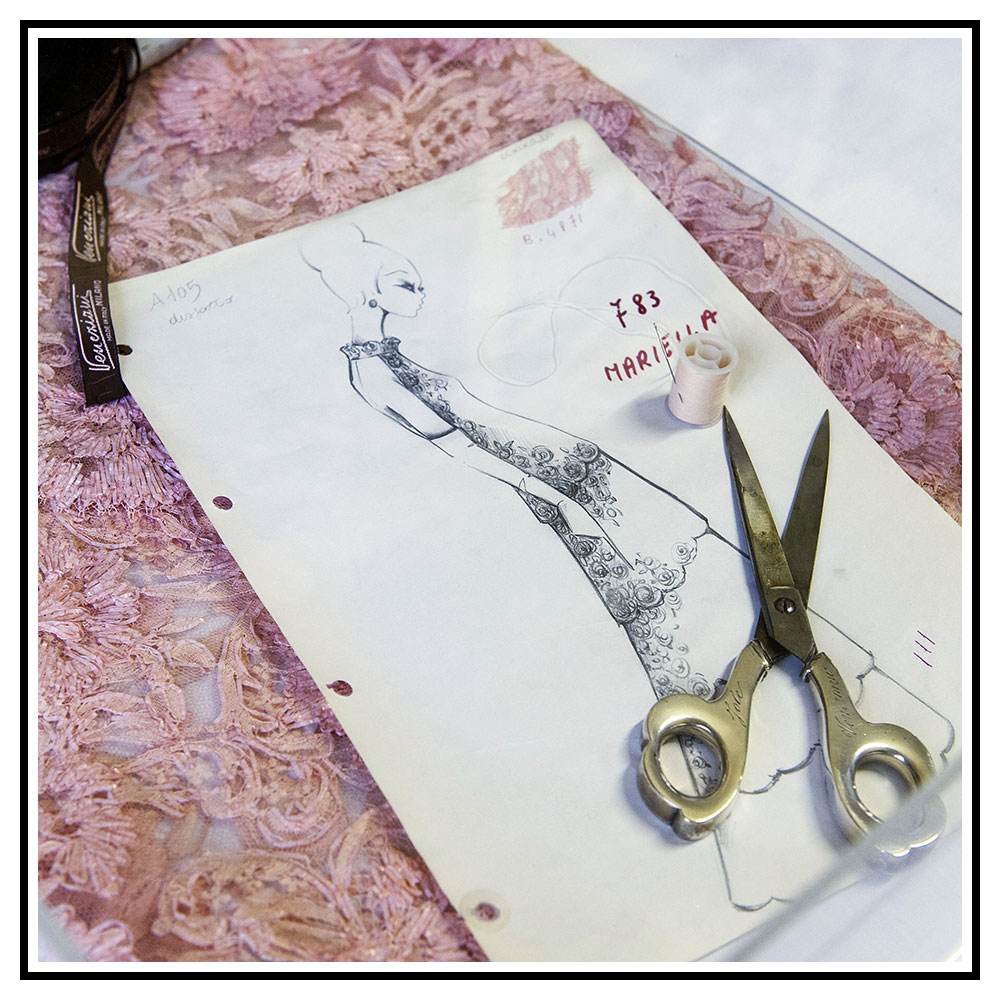

The memory of Jolanda Veneziani (Taranto 1901 – Milan 1989), leader of the birth and establishment of Italian fashion in the 1950s and ‘60s, is entrusted to the very rich and extraordinary archive that documents her life and work, safeguarded and valued thanks to exemplary classification and conservation criteria by the Fondazione Bano in Palazzo Zabarella in Padua. It is a kind of magic kaleidoscope that takes us back on waves of nostalgia to the enchantment of that period through various materials: splendid dresses and equally precious accessories, figurines that remind us of an inexhaustible creativity, newspaper cuttings and magazine covers that confirm her fame around the world, films in which the people, places, parades and events live again, and above all a collection of about 2000 period photos, many of an astonishing beauty, like those taken through the lenses of great photographers.

The real interpreter of the the Italian miracle.

Veneziani, who arrived in what was to become her city at the age of six, made a name for herself on the Milan scene from the second half of the 1930s. She then definitively established herself in the postwar period with her creative and entrepreneurial talents, when ‘she was not only a great stylist, she not only wrapped the most important international women and entire dynasties in furs with one-off collector’s garments, she was not only the pioneer of colour, of the working of tweed and of processes that removed kilos of weight from these garments, she was not only the first to create an industrial collection for Eurofour, with two-coloured sports jackets, she was not only the consultant who changed the dark colours of the Alfa Romeo into other, more feminine ones, and an advisor to numerous fabric companies. She was all this but, at work and in society, she was the real representative, the real interpreter of the years of the Italian miracle, of that boom, possibly imprudent, but of magical, vital impulses’ (Maria Pezzi 1999). Her triumph had many stages. In particular the legendary fashion parades in the Sala Bianca at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence where, according to an excellent witness like Dino Buzzati, the appearance on the catwalk in 1963 of her garments, distinguished ‘by luxury, with lavish use of the most expensive fabrics like vicugna and cashmere’, and of the very precious skins of mink, jaguar, leopard, black panther, ocelot and sable was ‘a small festival of the economic miracle, so stated and witty that it was unable to scandalise’.

Triumph and sunset of an era.

Da Milano, che garantiva un fecondo legame tra la moda e l’industria, la Veneziani ha contribuito alla nascita di una linea italiana, il “Made in Italy”, che a partire dalla memorabile sfilata organizzata nel 1951 da Giovanni Battista Giorgini nel proprio palazzo fiorentino, dove furono coinvolti tredici sarti da allora chiamati “i tredici apostoli della moda italiana”, riuscirà a delinearsi come alternativa a quella che era stata fino ad allora l’egemonia francese ed a imporsi nel mercato più importante, quello americano. Fu lei soprattutto a capire che gli americani desideravano “qualcosa di semplice e, già nel 1951, creò la seconda linea Veneziani Sport, una sorta di prêt-à-porter” (Sofia Gnoli 2012) dove trionfò un impermeabile bianco con cappello da pioggia destinato a battere il record di vendite e diventare nella stagione immediatamente successiva un capo indispensabile per le donne americane. Idolatrata dalle grandi riviste come “Vogue” e “Harper’s Bazaar” - nel 1952 “Life” le dedicò la copertina – riuscì a imporre e far riconoscere al mondo il suo stile scabro, essenziale, modernissimo che si avvicina a quello di Capucci. Tutto questo doveva durare sino a quando fu il sistema dell’alta moda ad entrare, già negli anni Sessanta, in crisi. Una crisi che la stessa Veneziani imputerà soprattutto al fatto che “si è lasciata troppa libertà alle donne nel loro modo di vestire: tutto è permesso, qualunque stile, qualsiasi linea; non esiste più una moda, vi sono cento mode e mille variazioni”. Ma la vera fine verrà decretata dal fatidico 1968 con “le uova lanciate sugli abiti di Jole Veneziani e degli altri creatori italiani alla «prima» della Scala”. Si avvertì subito come fosse tramontata un’epoca, “cambiato il costume, mutata la moda, nati altri stili. E Milano, definitivamente, sia diventata un’altra città. Più internazionale, sicuramente. Più democratica, anche. Ma assai meno lieta. E certo più distratta, meno tradizionalista e conservatrice. Più crudele” (Edgarda Ferri 1980). From Milan, which guaranteed a fertile link between fashion and industry, Veneziani contributed to the birth of an Italian line, labelled ‘Made in Italy’. Starting from the memorable fashion parade organised by Giovanni Battista Giorgini in his own Florentine palazzo in 1951, involving thirteen dressmakers who were from then on known as the ‘thirteen apostles of Italian fashion’, it managed to emerge as an alternative to what had until then been French dominance and establish itself on the most important market, the American one. It was mainly she who understood that the Americans wanted ‘something simple, and already in 1951 she created a second line called Veneziani Sport, a kind of prêt-à-porter’ (Sofia Gnoli 2012) where a white raincoat with rain hat triumphed and beat the sales record, becoming an indispensable garment for American women in the next season. Idolised by big magazines like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar - in 1952 she was on the cover of Life - she managed to make a name for herself and achieve world renown for her austere, essential, very modern style, which approached that of Capucci. All this was to continue until the high fashion system itself began to run into difficulties in the 1960s. Veneziani herself mainly blamed these on the fact that ‘women have been given too much freedom in their way of dressing: everything is permitted, any style, any line; there is no longer one fashion, there are a hundred fashions and a thousand variations’. But the real end was to be decreed by the fateful 1968 with ‘eggs thrown at Jole Veneziani’s dresses and those of other Italian creators at the La Scala premier’. It was immediately apparent that an epoch had come to an end, ‘custom has changed, fashion has altered, other styles have appeared. And Milan, definitively, has become a different city. More international, certainly. More democratic, too. But quite a lot less cheerful. And certainly more thoughtless, less traditionalist and conservative. More heartless’ (Edgarda Ferri 1980).